Ready to turn insight into action?

We help organisations transform ideas into measurable results with strategies that work in the real world. Let’s talk about how we can solve your most complex supply chain challenges.

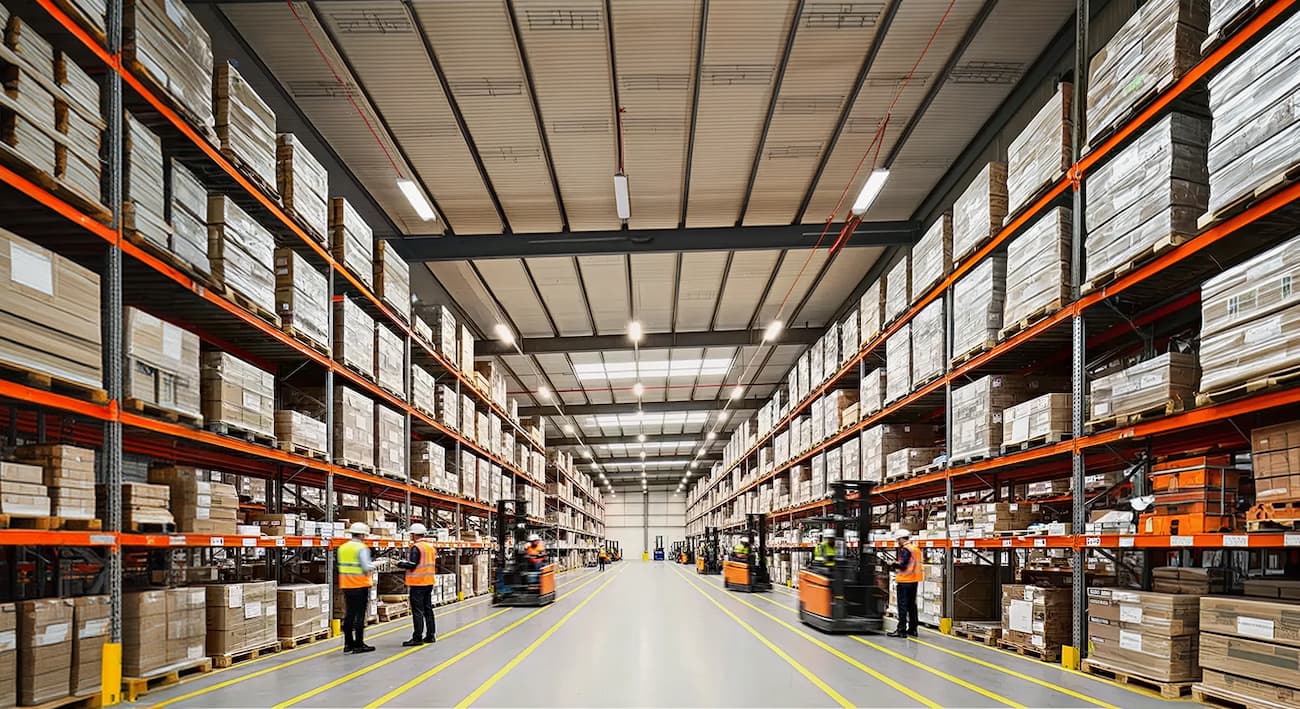

Warehouse, Cross Dock and Loading Dock Design

The unglamorous end of the building that quietly makes or breaks safety, service and cost

It’s early. The day shift hasn’t even fully clocked on, but the yard is already tense. A couple of trucks arrive “a bit early” to jump the queue. Another is late and insists they’ll be unloaded first because they’ve got a tight run. A pallet has been left in the truck lane because there’s nowhere else to stage it. Forklifts are weaving through pedestrians. Someone’s holding a door open with a bin. Everyone’s doing their best — but you can feel it: the dock is running the operation, not the other way around.

If that sounds familiar, you’re not alone. Across Australia, many sites run on a mix of good intent, local knowledge and workarounds that have evolved over time. The problem is, workarounds become the operating model, and once that happens, safety risk rises, service gets noisy, and costs creep in everywhere: labour inefficiency, damage, claims, missed deliveries, urgent freight, rework and fatigue.

The good news is that warehouse, cross dock and loading dock design are solvable. Not by “drawing a nicer layout”, but by designing the facility as a system: space, flow, equipment, technology, and the rules that govern it.

This article walks through:

- what “good” looks like for warehouse design, cross dock design and loading dock design

- the design decisions that matter most (and the ones that look important but aren’t)

- common traps that create congestion and WHS exposure

- how to link design choices to practical operating outcomes

- how Trace Consultants can help you go from concept to a facility that actually runs like the picture

Quick definitions (because these get mixed up)

Warehouse design

A warehouse supports storage plus handling: receivals, putaway, replenishment, picking, packing, dispatch, returns and exceptions. A good warehouse design balances:

- throughput (how much moves)

- inventory profile (how much sits, and where)

- service promise (how fast you need to deliver)

- labour and equipment

- resilience for peak, disruption and growth

Cross dock design

A cross dock is designed for flow-through: minimal storage, rapid transfer from inbound to outbound. In a true cross dock, dwell time is measured in hours, not days. Cross docks succeed when variability is managed and the sorting method matches outbound needs.

Loading dock design

A loading dock is the interface between road transport and the facility. It’s where variability enters your system, where WHS risks concentrate, and where minor design shortcomings get amplified daily. Done well, the dock becomes a stable, predictable “engine room”. Done poorly, it becomes the bottleneck that dominates everything.

Part 1: Warehouse design that stays safe and productive under pressure

Warehouse design isn’t just about racking and aisle widths. The best sites start with the operating intent and work backwards.

1) Start with flows, not the footprint

Before you choose doors or aisle layouts, get clear on the flows:

- inbound sources (suppliers, ports, inter-DC transfers, manufacturing)

- outbound channels (stores, e-commerce, wholesale, site supply)

- unit profiles (pallet, carton, tote, each-pick)

- peak patterns (day-of-week, promotions, seasonality, shutdown periods)

Then identify your dominant movement types:

- fast movers vs slow movers

- pallet in/pallet out vs break-pack vs each-pick

- temperature zones (ambient, chilled, frozen)

- value-add and exceptions (kitting, labelling, QA hold, quarantine, damages, returns)

If you can’t explain your top three flows in a few sentences, the warehouse will end up “multi-purpose” in the worst way — meaning congestion, double-handling and constant reshuffling.

2) Make staging explicit (and size it honestly)

Staging is where good operations go to die when it’s undersized.

Most sites “have staging” — it just spills into walkways, fire exits, dock aprons, or the nearest bit of empty floor. That’s not staging; that’s unmanaged storage.

Good design makes staging deliberate:

- inbound staging zones separate from outbound marshalling

- clear, protected pedestrian routes that remain safe even when busy

- defined overflow strategy for peak (where it goes, how it is controlled, who authorises it)

A simple test: if your dock or pick areas rely on staging being empty to stay safe, it won’t stay safe.

3) Design receipting for accuracy, not just speed

Receipting errors are expensive because they ripple into:

- inventory integrity and stock availability

- customer service failures

- supplier disputes and claims

- rework labour and “mystery hunting”

- expedited freight and late-night fixes

Design implications:

- a clear receiving “process spine”: check-in → unload → verify → label → putaway

- adequate space for exception handling (damages, quarantine, QA hold, temperature breaches)

- lighting and visibility fit for scanning and verification

- technology points planned into the workflow (scanning, weigh/measure if needed, photo capture for damages)

Speed is useless if it produces inaccurate stock.

4) Racking, aisle widths and equipment choices should follow the inventory profile

You don’t pick racking; your inventory does.

Key factors:

- pallet types and weights

- SKU velocity distribution (how many fast movers vs long tail)

- replenishment method (bulk to pick face, forward pick, case pick, each pick)

- equipment type (reach trucks, counterbalance, VNA, turret trucks, pallet jacks)

- safety and visibility constraints

A warehouse that mixes incompatible equipment and aisle designs often ends up with “informal rules” that only exist in someone’s head — and those rules break under peak pressure.

5) Don’t forget the “support spaces” that keep the operation stable

Many warehouses under-invest in the spaces that keep people and equipment functioning:

- battery charging areas and ventilation

- MHE parking and maintenance space

- amenities sized for workforce peaks

- training areas and induction points

- IT/telecoms rooms and redundancy planning

- PPE stations and safety equipment placement

When these are missing, they get improvised into operational space — and congestion grows.

6) Design for expansion without reinventing the whole site

If growth is likely, plan for it:

- an expansion path for racking and pick faces

- capacity to add doors later

- knock-out panels or future structural allowances

- yard space that can accommodate more movements without road spillback

- flexibility for future automation (even if you don’t install it now)

The cheapest expansion is the one you planned for. The most expensive is the one you “didn’t think you’d need” and now have to retrofit around live operations.

Part 2: Cross dock design — fast flow, but only if you control variability

Cross docking looks brilliant in a strategy deck: less inventory, fewer touches, faster throughput. In practice, it succeeds when:

- inbound arrival variability is actively managed

- product presentation is consistent (labels, pallet quality, ASN accuracy where applicable)

- the sorting method matches outbound requirements

- there are clear rules for exceptions and late movements

When cross docking makes sense

Cross docking can be effective when:

- inbound supply is stable enough to plan against

- product is already allocated (or can be allocated rapidly) to outbound demand

- the volume density is high enough to keep lanes flowing

- you have consistent packaging and labelling standards

It struggles when:

- inbound is lumpy and unpredictable

- product requires long QA holds or frequent rework

- outbound demand is micro-batched with high fragmentation

- the site becomes a warehouse that pretends it’s a cross dock (and ends up doing both poorly)

Layout choices that matter

Common layouts:

- I-shape: inbound one side, outbound the other — clean flow, but longer travel

- U-shape: inbound/outbound on the same side — can reduce travel and share resources, but increases yard complexity if unmanaged

- T/L-shape: used for constrained sites or phased expansions

Key decisions:

- inbound vs outbound door allocation

- lane depth and the number of sort lanes required

- staging buffers that protect outbound departures

- exception handling zones (damages, missing labels, overs/shorts)

- temperature control requirements (cross docking chilled/frozen adds complexity quickly)

Sorting methods and “touches”

Cross docks often fail because the number of touches wasn’t honestly modelled.

Sorting options include:

- manual “put-to-lane” using pallet jacks or forklifts

- pallet-level sort with dedicated marshalling lanes

- carton/tote sort with conveyors or put walls (when volume and SKU mix justify it)

- hybrid designs where fast movers and promotional lines use different flows

A cross dock should feel calm, even when busy. If it requires constant firefighting, the layout and rules are doing the fighting — not just the people.

The critical bit: rules for variability

Ask these early:

- What happens if an outbound truck is late?

- What’s the cut-off time for same-day transfer?

- Where does overflow go (and who authorises it)?

- What’s held, what’s pushed through, and what triggers escalation?

- What’s the process for supplier non-conformance (labels, pallet quality, timing)?

If you can’t answer these, the facility will answer them for you — and you won’t like the answer.

Part 3: Loading dock design — where safety, service and cost collide

Warehouses get the attention. Cross docks get the excitement. But loading docks decide whether operations are safe and predictable or chaotic and risky.

A useful principle: a well-designed dock sets the rhythm. Trucks don’t “arrive whenever”. They arrive into a controlled system with capacity, rules and accountability.

1) Separate people and vehicles by design

In dock environments, the goal isn’t “be careful”. The goal is to design-out conflicts.

Practical design elements include:

- fixed pedestrian walkways with physical barriers

- dedicated forklift travel paths separated from foot traffic

- defined crossing points (and minimised crossings where possible)

- clear line marking and standardised signage

- lighting designed for early/late operations and poor-weather visibility

- dock edge protection, handrails and anti-slip surfaces where needed

If your safety plan depends on “everyone remembering to do the right thing” during peak congestion, it’s not a safety plan — it’s a hope.

2) Plan doors, levellers and restraints for your fleet reality

Door design should match your vehicle mix:

- rigid trucks, semi-trailers, B-doubles (where applicable), vans, couriers

- tailgate vs dock-height requirements

- palletised vs hand unloads

- temperature control needs (dock seals, air curtains, rapid doors)

Core considerations:

- appropriate dock levellers rated for loads and frequency

- vehicle restraints or procedural controls to prevent drive-offs (depending on site policy and risk profile)

- bumpers and door protection that reduce damage and maintenance

- clear dock numbering and bay assignment standards

- door widths and heights suited to your pallets, cages and MHE

3) Staging is a design decision — not a daily improvisation

The fastest way to create an unsafe dock is to let it become a storage area.

A good dock design has:

- inbound staging sized for realistic peaks

- outbound marshalling sized for realistic peaks

- a defined “clean dock” standard (what’s allowed on the dock, what’s not)

- overflow space that doesn’t compromise pedestrian routes or emergency access

A simple operational rule often works: if it stays on the dock longer than the shift, it’s an exception that needs attention.

4) Dock booking and time-slot discipline are not optional at scale

Without controlled arrivals, docks become a queue-management problem instead of a throughput system.

Dock booking maturity often moves through stages:

- reactive, ad-hoc arrivals, manual check-in, inconsistent turnaround, unclear priorities

- scheduled time slots, bay assignment rules, measured turnaround, accountable ownership

- integrated yard and dock visibility (ETAs, alerts, conformance reporting), with continuous improvement routines

Even modest improvements — enforced time slots and clear priorities — can stabilise flow quickly and reduce congestion.

5) Treat the yard as part of the dock system

You can have a beautiful internal layout and still fail because the yard can’t breathe.

Australian yard realities to design for:

- heavy vehicle turning circles and swept paths

- queue capacity to avoid spillback onto public roads

- noise and curfew constraints (site-by-site)

- driver amenities and fatigue management considerations

- access control and security screening in certain precincts

- contractor movements, waste collection and returns

Key yard design elements:

- separate inbound and outbound routes where possible

- adequate queuing and marshalling space

- clear sight lines at intersections

- safe pedestrian access routes that avoid crossing live traffic lanes

- designated areas for paperwork, check-in or digital kiosks (if used)

6) Don’t ignore “non-core” movements: waste, returns, pallets and cages

Many docks become congested because they were designed only for inbound deliveries — while waste movements, returns, packaging, cages, pallets and contractor tasks fight for the same space.

If waste collection shares the same constrained dock lanes as high-frequency deliveries, congestion and risk rise quickly. Design implications include:

- dedicated waste holding areas and safe access routes

- compactor placement that doesn’t block truck movements

- defined windows for waste collection where possible

- clear ownership of waste flow and contractor controls

Docks that run well treat these movements as first-class citizens in the design.

The operating model is part of the design (whether you like it or not)

A dock isn’t “finished” when the concrete cures. The facility will be shaped daily by:

- who owns the dock and makes real-time decisions

- how arrivals are controlled

- how exceptions are handled

- how supplier and carrier conformance is managed

- what gets measured and acted on

The Dock Manager role: a high-leverage stabiliser

Sites with consistent dock performance typically have clear ownership:

- safety controls and enforcement

- bay allocation and priority decisions

- staging discipline and clean dock standards

- incident and near miss routines

- turnaround measurement and improvement actions

Without ownership, the dock becomes democratic — and that usually means it’s run by urgency rather than rules.

What to measure (so the dock improves rather than repeats itself)

Practical dock KPIs include:

- truck turnaround time (by carrier and by time slot)

- booking conformance (early/late arrivals)

- bay utilisation

- dwell time by supplier type (palletised vs hand unload)

- receipting accuracy and exceptions

- damage rates and claims

- safety observations and near misses

The point isn’t to create a report. The point is to create a rhythm: review, action, improvement.

Common traps (and how to avoid them)

Trap 1: Spending on CAPEX to cover operating model gaps

If arrivals are uncontrolled and ownership is unclear, redesigning the dock might just create a bigger space for the same chaos. Design and operating model need to be developed together.

Trap 2: Under-sizing for average day

Safety risk and congestion don’t rise linearly — they spike when capacity tightens. Design for peak, and design how you’ll manage peak.

Trap 3: Treating “temporary staging” as acceptable

Temporary becomes permanent quickly. If your layout requires constant reshuffling to stay safe, it’s a warning sign.

Trap 4: Forgetting exception flows

Damages, quarantine, QA hold, missing labels, returns, and rework will happen. If you don’t design a place for them, they’ll happen in the worst possible place: walkways and dock lanes.

Trap 5: Designing a cross dock without controlling variability

Cross docks are unforgiving. They need arrival discipline, clear cut-offs, and a sorting approach that matches the outbound promise.

An anonymised example: when dock and “other movements” are designed as a system

In a recent engagement in a large, complex precinct-style operation, congestion and safety exposure at the loading dock were driven as much by “non-core” movements as by deliveries — particularly waste handling and contractor flows sharing constrained space.

By redesigning the end-to-end flow (including how and when waste movements occurred, where materials were held, and how collections were governed) the client achieved a meaningful uplift in operational control and reduced overall waste costs by around 32% (anonymised, results vary by site and baseline). The bigger takeaway wasn’t just the savings — it was that dock performance improved when every movement was treated as part of one system, not a collection of separate problems.

Practical design checklist (use this before you approve any concept)

Warehouse and cross dock

- What are the top 3 flows, and can you trace them without crossing hazards or bottlenecks?

- What does peak look like — and where does overflow go?

- What proportion of volume is pallet vs carton vs each, today and in 3 years?

- Where do exceptions go (quarantine, QA, damages, returns), and are they out of the main flow?

- Does the layout support safe, repeatable work, or does it rely on “common sense” under pressure?

- Can the warehouse expand without relocating core operations?

Loading dock and yard

- Are pedestrians and vehicles separated by design?

- Are staging and marshalling areas sized for realistic peaks?

- Do you have a clean dock standard, and can you keep it under pressure?

- Is dock booking in place (or can it be), and are time slots enforced?

- Who owns the dock end-to-end every day?

- Are waste, returns, pallets, cages and contractor movements designed into the flow?

- Can the yard queue without spilling onto public roads?

- Do your doors, levellers and equipment match your vehicle mix?

How Trace Consultants can help

Warehouse, cross dock and loading dock projects succeed when design, operations and technology are aligned. Trace supports clients across the full journey — from early strategy through to implementation and stabilisation.

1) Strategy and requirements definition

- clarify your service promise and channel strategy

- translate operational intent into a practical requirements set (a functional brief that operations can stand behind)

- define when cross docking is truly viable and what must be true to make it work

2) Capacity modelling and option evaluation

- model throughput, door counts, bay utilisation, staging requirements and yard flow

- stress-test growth scenarios and peak conditions

- compare options with clear trade-offs (CAPEX, labour, safety, resilience, expandability)

3) Dock operating model, governance and KPIs

- design dock booking and time-slot policies that are enforceable

- define dock ownership and decision rights

- create practical routines for performance management and continuous improvement

- lift supplier and carrier conformance without disrupting relationships

4) Technology enablement (kept practical)

- advise on yard, dock and transport visibility options that suit your environment

- support integration thinking across WMS/TMS/YMS where relevant

- design reporting that drives action (not just dashboards)

5) WHS and compliance embedded into the design

- safer segregation of people and vehicles

- controls that reduce reliance on individual behaviour

- operational procedures that match the physical reality of the site

- alignment to Chain of Responsibility obligations in day-to-day practice (not just in policy documents)

6) Implementation support that lands

- stakeholder alignment across operations, property, safety and procurement

- cutover planning and stabilisation support

- training, induction and operational readiness

The goal is simple: a facility that runs safely and predictably on a normal Tuesday — and doesn’t fall apart on a peak Friday.

Frequently asked questions

What’s the biggest mistake organisations make with loading dock design?

Treating the dock as a “doorway” rather than a system. The dock needs controlled arrivals, defined staging, clear ownership, and safe segregation — not just more space.

How do I know if cross docking is right for us?

If inbound is highly variable, product presentation is inconsistent, or outbound is micro-batched and fragmented, cross docking can become expensive chaos. It works best when allocation is clear, arrivals are disciplined, and there’s enough volume density to keep lanes flowing.

Can we improve dock performance without rebuilding?

Often, yes. Booking discipline, time-slot enforcement, staging rules, and clear dock ownership can stabilise flow quickly. Physical changes then become targeted and worthwhile, rather than a blunt instrument.

How do we design for growth when we’re not sure what growth looks like?

Use scenarios. Design a base case that runs well today, and a growth case that shows what needs to change (doors, staging, yard, automation readiness). Build “expansion paths” into the layout.

Closing thought

The warehouse gets the attention. The cross dock gets the ambition. But the loading dock is where reality shows up — in safety risks, queues, congestion and cost-to-serve.

If your volumes grew by 25% next year, would your dock get safer and more controlled — or would it just get louder?

If you want a clear answer (and a practical path forward), Trace Consultants can help you design a warehouse, cross dock and loading dock that are fit-for-purpose, safe by design, and built to scale.

Ready to turn insight into action?

We help organisations transform ideas into measurable results with strategies that work in the real world. Let’s talk about how we can solve your most complex supply chain challenges.